Bryan Caplan teaches Fossil Future — Part 2

Audio and transcript of economist Bryan Caplan's lecture on energy and environmental policy, focusing on my book Fossil Future

Economist and George Mason University Professor Bryan Caplan has been one of the most prolific promoters of my book Fossil Future—see “Read Fossil Future,” “Alex Epstein’s Steelmen,” “Let’s Audit Alex Epstein,” and “Fossil Future: The Epstein/Caplan/Hanson Conversation.” And last semester, Bryan taught Fossil Future in two lectures of his economics and public policy class.

I am very grateful that Bryan recorded these lectures, because they are awesome. Bryan is a great teacher, and he comes up with many new ways of explaining the ideas in Fossil Future. I think many of my readers will enjoy hearing/reading many of my ideas from a new perspective, with new examples.

Here is the audio of Bryan’s second lecture, followed by a transcript. (I have added footnotes where I thought a factual clarification would be beneficial.)

Bryan Caplan:

All right, everybody. Let's get started. I believe that you're now able to go and fill out the evaluations online. Did you get an email about this from GMU? All right, so this is your chance to go and say how bad I was or otherwise, how good I was, how hard I tried, or I didn't try it all. Whatever your opinion is, you may express it there. All right, let's just review what we've done. All right, so we talked about energy and why we need it because it's too hard to carry suitcases yourself. That's why. If you ever had to do this, two suitcases for a distance, two wow, I can barely do anything, but I have a friend who has a car that barely works and it's much better than I am. All right? As I said, then, throughout most of human history, humans did figure out some better energy sources thousands and thousands of years ago, like wood, domestic animals, but those aren't that great either. And then a few hundred years ago, people said, “hey, we could go and burn coal.”

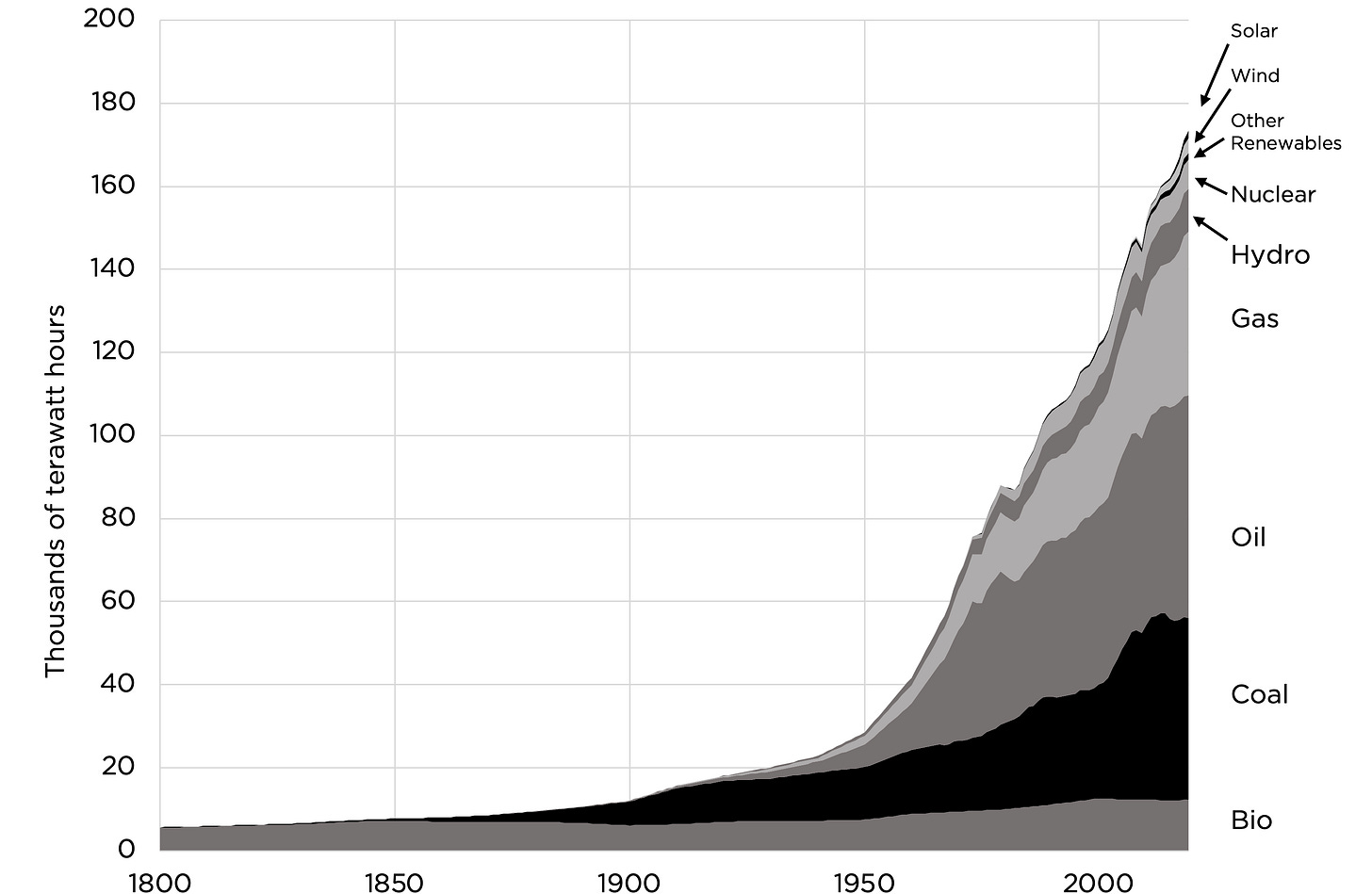

And they figured out amazing things to do with coal, like make steamships. All right? And then over time, we got oil, natural gas, nuclear energy, electricity, transportation, residential heating, industrial heating. We took a look at this graph of what's been going on. The more you study it, the more surprising it really is. As you can see that even when people get coal, it takes a really long time for coal to actually become more important than traditional sources. This is because this is the whole planet. It's the whole planet. So more modern energy sources start in a few small countries like England, and they spread very gradually.1

But you really have to get to about 1910 before coal is more important than what he calls biomass—wood, and so on. And then oil takes off. But oil takes a really long time to become important, too. It's after World War II that oil is more important than coal. Still, most energy is coming from coal at this point. And then we go into the modern world. Now, coal, oil and natural gas are about equally important. Looked for a while like nuclear was going to take off, but then it just stopped at a very moderate level. But now solar and wind remain very unimportant despite all propaganda. If it ever looks like they are important, it's because they first only show you electricity, not all energy. So we don't have electric planes. We don't have electric cargo ships. And then secondly, they're showing you the countries that use them the most, like Denmark. So if you go and do those two adjustments, then wind and solar could look important, but they're not important globally.

And how do countries like Denmark do it? With very heavy subsidies. There's no country where they just allow a free market and then we see solar, wind doing well. All right? Then we talked about why it is that people really like fossil fuels so much? There's so much anger against them, but people keep using them. See, in China, in school they tell you the fossil fuels are terrible and they're destroying our planet or not? No. Okay, but in America, do they tell you fossil fuels are terrible and they're just destroying our planet? Yes. This is one of the main things we teach kids is they're terrible and they're destroying our planet. And yet kids hear this and they go and put gas in their car. Why are people doing it?

Well, the answer is that there are standard traits for good energy sources. Concentration. You want to get a lot of energy in a small area. Like I said, gasoline has got 31,000 Calories per gallon. If a human being could survive on gasoline, which they can't, but if you could digest gasoline, two gallons a month is all you would need. Secondly, reliable. Fossil fuels can be burned anywhere. There's nowhere you cannot burn gasoline. Works everywhere and then abundant. There's been a lot of fears running out, but we keep finding more sources. And if you just look at what we even know. We've got lots. But the more important point is when someone says, “well, we only know 30 years, we'll be out in 30 years.” That's like saying we only have three days left worth of breakfast cereal.

We're going to have no cereal after three days from now. It's like, well, how about we go to the store and find some? Finding new fossil fuels is not as easy as going to the store, but it's not that hard, either. There are so many ways to do it. Fracking in the Dakotas of the United States is the most recent one. The United States in a very short time went from being a net importer of fossil fuels to being an exporter because we just adopted this new technology for extracting it.2

All right, and then finally, as Epstein points out, we have spent about 200 years figuring out how to use fossil fuels. So we have gotten very good at it. All right, nuclear is way better than fossil fuels by the first three measures. It's got better concentration, better reliability, better abundance. Like I said, 18 billion Calories per gram. This amount of uranium, if human beings could eat nuclear power, would feed the whole world for I think a day or two, a crazy amount. All right. But we do have way less experience figuring out how to harness nuclear power. A lot less experience. We just don't use it for very much. You get good at things by doing things, but the really big deal is regulation of nuclear power is very strict. United States is less strict than a lot of countries, but still very strict. Like I said, the last nuclear plant to be built opened in 2016, previous one was 1996.3

Okay. And important to remember, there are some subsidies for nuclear power, but the penalties are much bigger than the subsidies. The net is extreme penalties. And if we wanted to just go and replace what we got, we would need to start building at 500 times the current rate. So instead of two plants in 20 years, we would need to have a thousand plants in 20 years, which would be a big change. All right? Now, on the other hand, renewable energy. All kinds of love the people express for renewable energy, but the problem is they lack these traits. They're diffuse. The amount of solar energy you can get in one square meter is not much. You need to have an enormous solar farm to get much energy. Same for wind. You need to have a lot of windmills to get a good amount of wind power, unreliable, solar, it only works when the sun is shining.

Wind only works when the wind is blowing. You've got batteries to give you a bit of extra extension, but batteries don't work very well either. And yeah, then they're not naturally abundant. These have been subsidized for decades. There's still barely anything. All right, so could the unreliability of solar and wind be solved? In theory, yes. Yes. But you have to do something amazing that we haven't done yet. And it's mostly wishful thinking. You think it will happen soon. We need to have much better batteries, not just batteries that are twice as good or 10 times as good. We need batteries that are a thousand times as good, a million times as good as we've got, right? Or you need to just have a grid that is enormous. We need to connect enormous continents so that there's always some place the sun is shining. And let's see, here we go.4

Yeah, Eurasia, I think their sun never fully sets on Eurasia. So you could be powering Japan with solar power, with solar panels from Spain for all connected, right? You could imagine doing that. However, again, this would require incredible investments, the likes of which the world has never seen. All right? Okay. Now like I said, usually people focus on electricity, and if they want to make you think that there's hope, they will only focus on electricity. That's only one thing that we need power for. All right? So using wind or solar for heavy transportation, cargo ships, or airplanes. For now, it's hopeless. No one's even trying to do this, right? Or using them for industrial heating, like powering steel mills with wind is a fantasy, for now, but for the foreseeable future. And then there is this well, they're getting there. They're getting there. There's no country that uses them much unless they're heavily subsidized.5

Could it all change? Could everything change? Yeah, it could. But if someone said, “hey, bet me, bet me that we will be flying around in solar-powered planes in 10 years.” Don't give them your money. Well, it actually depends. If the other person says, “I bet it will then give them your money because they're going to lose, almost certainly.” All right, now, let's point to hydro. Hydro. There is no reason on earth to say it is not renewable, but usually, it doesn't get counted as renewable because it means you have to go in dammed rivers and disturb plants and animals. But obviously, it is a renewable energy. If sun and wind count, how can rain not count as renewable energy? Of course, it does, but two problems. One is you need to be close to it.

So some places are close to enormous rivers then hydro is fantastic. But the other problem is that's heavily regulated too. It's hard to go and get permission to build dams. And so we barely do that anymore. All right, now that's review. Next part. Okay, so fossil fuels, as you know, are very unpopular. A lot of people complain, right? What's interesting is they usually complain without ever mentioning why we use it. If all that we could say about them were the complaints, then it'd be like, well, why has anyone used this terrible stuff? Well, the reason why we use it is it great as energy, but maybe it's got a bunch of other serious problems that are so serious that we have to find something else, maybe. But you can't even really have a decent conversation until you admit that it is fantastic as an energy source.

Gasoline is an incredible energy source. How can you deny it? It's why we use it. All right? So they've got these problems that many people complained about. The classic ones, there's air and water pollution. All right? So is anyone in a city with really bad air back home in China? Your air is okay, right? Oh yeah, I was asking. But there are parts of China where the air is very bad, right? Yeah, some very bad air. Do you have any relatives who's like, ah, I can't breathe. Ah, it's terrible. All right, so anyway, so we got coal burning. The early coal was terrible. Whole cities would be black with soot. If you go to Europe today, you can still see old cathedrals that are just black. I think that's just because they burn coal there for a hundred years. Now they don't do much anymore, but they just never cleaned the cathedrals.

So it looks like a terrible thing. It looks like it's made out of volcanic stone when it's not. All right. Now your modern fossil fuels are much cleaner. Even coal we have is much cleaner now. We have technologies to reduce the amount of black stuff that goes to the air. There's a lot of researchers who say still, even the low-level air pollution we have is really bad. There's some dispute on that, but at least there's some smart people looked at it and said, yeah, this is doing a lot of harm to humans, but hardly anyone actually complains about the black stuff we put in the air anymore. Instead, the main theme you'll talk about is climate change. All right? So burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide, and at the level we're using, it's enough to warm the planet. You can actually see warming on Earth.

All right. And then many people worry it's not just that the world will get too hot and we will be uncomfortable, but rather it's going to cause a bunch of other problems. Storms, flooding. If we melt enough ice, then the world will flood. All right. Principle. You don't have to worry about icebergs melting because if ice is already in water and is already displaced as much water as it's going to, if it melts, that doesn't matter. But if it melts from Greenland, if it is ice on land and it melts and then goes into the oceans that does raise sea levels, all right? There's ocean acidification more. And then finally, there are some people who just say it's wrong to tamper with nature. Say, “look, it's not just about the bad effect on humans, it's about you have touched nature, it's sacred. Who are you to touch nature?”

All right. And again, if you think this is just a few weird people who are crazy, it's not. How can you explain why we got strict regulation of hydropower if people don't think that nature is sacred and you shouldn't touch it, or nuclear power? It's actually very safe, but there's still a lot of regulation, and normally environmentalists strongly support it. Not all, but some or most. Most. All right. Okay, and now we're ready to resume. All right. This is what is pretty crazy. There's even environmentalists who try to stop wind and solar. If you're an environmentalist, why do you stop wind and solar? Well, here's the problem. To get a good amount of wind or solar energy, you have to go and get an enormous area and fill it full of solar panels or windmills.

You could go and say, “hey, let's go and demolish a bunch of human cities and put windmills there.” But that's not going to be very popular. Right? So normally if you want to go and get 10 square miles of windmills, what will you do? You'll go out to where people don't live. And what do environmentalists call places people don't live? Starts with an N. Nature. All right? So you're going to destroy nature just so human beings can keep living with their electricity and so on. Okay. So that is something that is quite striking. But there really is environmental activism against putting in more solar panels because you need a large area, which means you have to go and disrupt a lot of nature. There's people complaining about windmills killing birds. So this is a case where it's like, geez, it's pretty hard to please you people. You're going to complain about anything we do other than just exist in a primitive state, doesn't seem too good or not important.

If people really value unspoiled nature, then cost-benefit analysis says we will take that into account. All right. So if there's an environmentalist who, just seeing a windmill in a forest causes me $10 worth of harm every time I look at it's like, all right, well, we better put that minus $10 of harm into our calculations when we decide what to do. All right. But remember social desirability bias. If someone says, “how much does it bother you when we clear-cut a forest in order to go and put in an oil pipeline?” What is the answer that sounds really bad? The answer that sounds really bad is: I don't care.

Chop down all the trees you want. It doesn't make any difference to me. So what? We chopped down a million trees, we got a billion trees more. Doesn't matter to me. I couldn't care less. That answer sounds terrible. Same one. It was like, well, what if we go and we put in a bunch of windmills and they kill a bunch of migratory birds? Birds die all the time. Who cares? Now, we have a lot of evidence that people actually don't care very much. Things like if you tell them a million birds died, or a billion birds died, people say about the same reaction. Million birds, billion birds, trillion birds, whatever. It's just birds. All right. You want to say something, but it's like terms of the numbers people don't seem very interested, all right? So anyway, it's unlikely that true willingness to pay is high.

If there is an oil pipeline in Alaska that spills, it'll be on the news and people are like, “Oh my God. This is terrible, that oil spilling all over Alaska.” The most sensible thing would be to say that's valuable oil, how we need that oil. But the normal reaction is spoiling the beautiful nature of Alaska, a nature that almost no one on earth will ever see because it's too far away from humans for them to ever get there. Anyone ever been to Alaska at all? Anyone ever been to rural Alaska? The remote area of Alaska? There's a few people who do it, but it's hardly any. And remember, you're doing cost-benefit analysis. If three people care, then how many people do we need to find out how much they care? Just three people. It's like, how much could you really care about it? The world is full of other problems.

This one thing, some oil in the middle of nowhere's going to bother you. All right. Seems unlikely that people actually care very much about harm to nature that no one ever sees or experiences. Harm to your breathing. It's easy to believe people care about that. Yeah, that's really bad if you're having trouble breathing, right? Let's see. Yeah, so smoking is still pretty high in China, right? Let me say this. Anyone ever been in a car with three people smoking? It's pretty bad. It's pretty bad. It's unpleasant. All right, so questions? Questions? Okay. All right. So these are negative externalities. Some of them could be very severe. Others probably just imaginary or almost imaginary. All right, but now, next one. All right, so we've got these negative externalities of energy, but what about positive externalities? Remember, when you're doing cost-benefit analysis, you always want to go and measure, add negative and positive externalities both.

And then what do we do? We add them, we add them. We got a negative, we got a positive. And then sums to what? That's the important question. All right. Remember, we already talked about the positive externalities of population. Externalities hardly anybody talks about, but they're obviously there. Things like when there's a larger population, there are more scientists to come up with new ideas that benefit us all. The country of Iceland has delivered almost no scientific advancements to mankind. Why? Well, per capita, Iceland is fine, but there's just so few people in Iceland, they don't really do anything. Nothing that's noticeable for humanity. All right. Okay, so anyway, energy's got positive externality or population has positive externalities. Energy also has positive externalities. What would these be? Well, here's one that is very well documented. Carbon dioxide is good for plants. Carbon dioxide is good for plants.

This you can show in a laboratory. You can create a little greenhouse dome over some plants and give them different levels of carbon dioxide. And you will see the more carbon dioxide the plants get, the more they will grow. Right? Now what happens when you put a lot of carbon dioxide all over the planet? Plants start growing better all over the planet. And how is plant growth good for humans? See, have you ever eaten a plant? Yes, we all eat plants, right? So yes. So that alone. So it is good for agriculture to have more carbon dioxide. Does this show that we should have as much carbon dioxide as possible for the plants? No, but it's something to put on the positive side when we are doing the math. All right. And then at least in some important cases, we know that positive externalities outweigh negative externalities.

How? Well, we can take a look at climate deaths. Yes. All right. Here is the actual data on fossil fuel use carbon and climate-related disaster deaths. Now, remember we've got hard proof that if you put enough carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, this will raise the global temperature noticeably, and that in turn will lead to some other problems. So things like you get more storms, more energy means more storms. You get warmer planet, you get more flooding. So these are things that if they're bad, can kill people. Right? So you turn on the TV and they'll say, massive flood kills 300 people. All right. Or a hurricane kills thousands of people, right? All right, so here is what we see for atmosphere of carbon dioxide going from for about the last a hundred years. So we have increased by about 35%. All right. Then take a look over here.6

Climate-related disaster deaths. This is deaths per million persons. So a hundred years ago, it was almost 2,500 per million were dying every year of climate-related deaths. All right? And then ‘30s goes down a bit, ‘40s goes down a bit, and then ‘50s, right? ‘50s we're at less than half of where we were in 1920s. Remember, this is for the planet. This is for the whole planet. Right? And then it goes down even more in the ‘70s. And now we're down to almost nothing. Almost no one on Earth is being killed by any kind of climate-related disaster now. All right, so what's going on? Well, the weather's not better. The weather is not better. Maybe it's worse. Probably it's a bit worse in terms of the dangerousness of the climate. So what is happening? Well, let's see. What do you think is happening?

You can tell pretty easily what countries do you think started having hardly any climate-related deaths first? It'll be like England, the United States, Germany, the richest countries in the world. And how is it that they avoid having climate-related deaths? To a large degree by using technology powered by fossil fuels. All right, that's pretty clear, right? That's the thing that has changed is the technology, right? And this is not just... Isn't it wonderful we have the Internet. The Internet's probably done very little for this. It's actually old-fashioned technology that goes and controls water, prevents flooding, moves people to safety quickly, versus also satellite technology. We get advanced warning, but all right. And then on the other hand, if you look, where are the countries where people still die from climate? They're the world's poorest countries. They're the world's poorest countries are the places where people still die from climate.

And what's going on there? In the world's poorest countries, they barely have any energy and barely any modern technology. So they are almost in the same world that people lived in a hundred years ago. Even there, at least they now get advanced warning from satellites and things like that. So rich countries are not going to go and build dams for them to prevent flooding, but they will go a little bit, but not much. But they will go and say, “hey, hurricane's coming. Haiti, you might want to get to high ground.” All right, so this is something where this does not mean that carbon dioxide emissions did not make the planet's climate worse. Probably did. But it does mean the net effect when we look at the negatives. How much have we messed up the climate versus how much have we improved the effects of the climate using these same technologies?

It looks like we've got not just a positive, it looks like a massive positive, right? Now, some people look at this and say, “well, how do you know it's not going to go back up?” All right, well, I guess we don't have any absolute proof, but if you had to bet, what would you say? Right? Do you think that in a hundred years we're going to be back to there? Seems pretty unlikely. It's imaginable, but unlikely. And when someone claims that there's going to be a mass reversal of a trend that we seem to understand pretty well. They should bet you, right? They should put some money on it. All right. Okay, so any questions about climate-related deaths and how we are actually much safer than ever? Okay. All right. Well, so carbon emissions are definitely warming the planet. So how is it possible that we got so much safer? Yeah, fossil fuels power the modern economy. And what does that do? It shelters us from harm. So if there's a hurricane and you are living in an old-fashioned straw hut, what happens?

You lose. First of all, you lose your home. And second of all, since you don't have protection, maybe you die, too. So first, your home gets destroyed, and then you get crushed under it. Or you get thrown into a tree and you die. Or a tree comes down on you and kills you. If you're living in a modern concrete skyscraper, do hurricanes knock those over? No, they don't. You get maybe a little flooding on the first floor, but you are not going to have your home collapse because of a hurricane. You might want to go and put wood in front of the windows and things like that, but your modern home is not going to be destroyed by a hurricane, all right, let's see. 20 years ago there was a hurricane. There was a hurricane here, and a lot of trees came down.

You see a few trees landing on people's houses and doing damage, but no one had their home destroyed. All right? And then also rescues people from harm, rescues people from harm. That does occur. If there is flooding, then you've got helicopters to come and rescue people from the flooding. Someone's sitting on their house, if the flooding is really bad, or you have boats come, not just a canoe, not just one that you power that way, which is not going to be too good, but like a real boat. Save people. All right, so that's what's going on. That's why we're so much safer from climate-related deaths. All right, so what about other positive externalities of fossil fuels? All right, well, for now, fossil fuels power our economy. Modern economies are powered by fossil fuels. Even in Denmark, they are still getting most of their energy from fossil fuels. They may be getting most of their electricity from something else, but when you fly into Denmark, you don't fly in on a wind-powered plane.

Flying. We power the modern economy. Guess what? That makes human beings rich. This modern economy means that we are able to fulfill not just our basic needs to fulfill a great many wants. And when human beings are rich, that means that we have extra resources. What do we do with extra resources? A lot of things. But one thing is we innovate. In a world where we all are on the edge of starvation, we don't have time. We don't have spare resources for scientists to investigate better ways of farming. But if we have lots of food, then we don't need everyone to work in agriculture. And that means there's extra people and they can go and think about how to make the world better. And this is the story of the last few hundred years. Used to be that almost everyone is just working for survival. If everyone's working for survival, things aren't going to improve much. Once you are well above survival, that's where you can say, we have extra resources to go and make the world better. And remember key thing about an idea.

One person on earth has an idea. That idea can be enjoyed by everyone on earth. One person writes a song, eight billion people can listen to that song on YouTube. That's what's so amazing about the modern world is that a good idea anywhere becomes a good idea everywhere, very quickly. All right. And then Epstein points out something that I never thought about. It's like even coal. The worst blackest coal that you had in the 19th century, even that has positive externalities. What? How? Well, you shouldn't compare coal to nothing. You should compare coal to what it replaced. Once we got rid of... Or once we got coal, what did we get rid of? Well, we got rid of dung and wood and domestic animals. Imagine what cities would be like if we still had several domestic animals per person.

They would be filthy, completely disgusting. Coal went and replaced animals and animal waste. Just imagine what it's like when you have lots of animals around. If you go to New York City, there is an area where you can get horse-drawn carriages. You can be in a carriage and a horse walks you around Central Park. It's fun to do once or twice. But imagine if every car was replaced with a couple of horses. It's very smelly and unpleasant. And of course, wood. Have you ever, ever, ever been to a campfire? And there's wood going, and the wind goes the wrong way. What happens when the wind goes the wrong way? You get a pile of smoke in your face and your eyes hurt. This is what coal replaced. Coal replaces wood. Wood is not clean. So in a lot of ways, coal was an improvement.

As bad as it was in the early years, coal is still replacing something even worse. All right. Now I've argued about this with Professor Tyler Cowen over there. I don't know if he's here today, but arguing with him a lot and he's saying, “look, we've got all these estimates showing that if we keep using fossil fuels, that this is going to reduce GDP in the future through a bunch of problems.” And I say, “well, compared to what?” It's like, yeah, compared to an imaginary fantasy world where we find something that is just as good as fossil fuels, except it doesn't make carbon. I'm like, wow, that's not very impressive, really. Okay, all right. So yeah, and especially where we do this costlessly, where we just happen to go and find something great. All right? Now Tyler's always saying, “look, what we really need is to have subsidies for us to find a good alternative energy.”

Sure, solar and wind aren't very good. We need to go and have the government spend a pile of money so we can find something that is good. We need to get something that works as well as fossil fuels without the problems. All right? Now, when you put it that way, it's like, well, I hope we don't need it because we probably won't get it. It's kind of a fantasy. Maybe. But can you rely upon that? Can you say, “look, the world's going to give us something just as good as fossil fuels without the problems”? Seems unlikely. But here's the really crazy thing. This is what's crazy. I'm talking about, we want something that's as good as fossil fuels without the problems. All right? Now when I say we're not going to find something like that, well, here's the thing. A hundred years ago, we already found it.

We already found something that is actually much better than fossil fuels and doesn't have these problems. Super-clean, super-safe, and yeah, it's called nuclear power. All right? We discovered it. It's like I said, a hundred years ago, people figured out how to do this almost a hundred years ago. All right? Yes. You know how World War II ended, right? Yes. Nuclear bombs were dropped on Japan. Nuclear bombs that were powered by nuclear power, all right? But anything that you can go and use to destroy a city, you can also use to move a ship, pretty much. Well, maybe not anything but close. All right, so yeah, we discovered this fantastic replacement for fossil fuels almost a century ago. And what has humanity done with nuclear power?7

A little bit. Not much. Really, most of the progress happened early on. So in the 1950s, we came up with nuclear-powered submarines. So basically you just put in some small amount of fuel in your submarine and you'd go for years, maybe even decades on one without refueling. It's an incredible technology. It is like magic. All right? And there was an attempt to go and start expanding. I think Sweden was a country where in the sixties and seventies they started doing a big switch, and then it stopped. Then it stopped. Why? So part of it is environmentalism. It's like this is... Don't mess with nature. Then another part is just crazy safety fears. Are fossil fuels totally safe? Of course not. People are continuing to die from coal in large numbers. Most obviously, coal miners, people who work in coal mines get horrible lung diseases that kill tens of thousands of people on Earth per year.8

So these technologies are not perfectly safe, but nuclear power is much safer. But when there is a nuclear accident, it gets global coverage. We don't go on TV and say, “hey, another a hundred people died from coal today.” Nobody cares about that. But a nuclear accident, even a nuclear accident that kills no one gets global attention and people panic. Number of people that were killed in Japan's Fukushima nuclear disaster 10 years ago? Zero. Number of people killed in the United States Three Mile Island disaster? Zero. Chernobyl, some hundreds of people. So again, that was the Soviet Union. Lots of bad stuff happened in the Soviet Union.

Okay. So anyway, once you understand how good nuclear power is, it's not just a question of we got to find something that's as good as fossil fuels without any problems. It's like, we got to do it again. We already did it once and then we just wasted this opportunity. And now Tyler's telling us we got to find something else. And I said, “look, how about we use the incredible technology we already found? We barely use it. Why not go and actually take advantage of that? It's a good idea, but people are very stubborn about it.” Which makes you think, suppose we did accomplish this incredible miracle of coming up with another technology that's as good as fossil fuels but doesn't have the problems? Is it possible we wouldn't use that either? There'd be some safety problem with it that kills five people a year.

But there's a big story about it. Or environmentalists say that's a terrible technology. Human beings were not meant to do that. Right now some people are getting excited about geothermal energy. If it started to actually work, which seems very unlikely on a large scale, but if it did start to work, what do you think people would do? Would they say, “hey, it's fine? Yay, problem solved.” Or would they say “maybe it causes earthquakes? We need to go and have a 30-year study to see whether it's causing earthquakes.” Yeah, I think it's more like that.

So say if we are really worried about fossil fuels, the sensible thing is to say, “all right, we've got a replacement. It works. Everyone complaining must now be regarded as terrible. Everyone who complains about nuclear power, you are terrible people. You're fools, shut up. We're not going to listen to you anymore. We're going to teach kids in school to hate you, and we're going to go fully on nuclear power.” That would make sense. All right.

Okay, so questions? Questions. I think I mentioned a famous director, Oliver Stone, has a new documentary about nuclear power that's coming out, and he's pro-nuclear-power. So he said some crazy things in the past. But anyway, so all is forgiven, Oliver. Everything you've ever done wrong, I don't care anymore, you are promoting nuclear power. That's good. Okay. All right. Questions? Questions. Of course, China is one of the best countries for nuclear power in the world right now. Yay. Go China. Yes, teach the world. Teach the world. All right. Okay. So now people who are realistic about climate change. People realistic about it will usually say, “all right, part of what we're going to do is adaptation. Adaptation.”

Who is unrealistic? Unrealistic people are those who say we're going to stop using fossil fuels today. It would just kill billions of people if we stop doing it today. Imagine if we just had no vehicles powered by fossil fuels today if you couldn't use them. Well, how is the food going to get harvested? How will food be transported? If we just stop using fossil fuels today, billions of people would starve to death. There's really no arguing against that. All right. So normally you'll see even the craziest people don't say stop today. They'll say, stop in 5 years or 10 years. Okay. How hard is that going to be to go and replace this entire system with solar and wind? Pretty much impossible once you remember, oh yeah, electricity isn't even the only thing that we need energy for. What are we? Are we going to get rid of airplanes because they cause carbon emissions?

Sounds really bad to live without airplanes. None of you guys would be here without airplanes, right? Good. You wouldn't be here. You might be here. You were. You're born in Virginia?

Student:

Yeah.

Bryan Caplan

All right, so you'd be here. Yeah, I guess I drove across the country to get here once, so I guess I could be here too. No, but I'd have to do it on a horse or something. So yeah, probably I'd still be in California. All right, anyway. But getting rid of it today is crazy. Getting rid of it in 5 years, 10 years, this is all crazy. Because even if you could replace the electricity, there's still all the other things that we use energy for where we don't have any remotely realistic replacement. Some of them, we don't have any replacement at all. There just is no such thing as a jumbo jet powered by renewable energy.

No one's even trying to do it. It's just a fantasy. All right. So realists will usually say, “look, we're going to do two things. We're going to cut down on our carbon emissions and then we're going to go and try to adapt to the climate problems that are going to happen. We're going to do some balance, we're going to cut back a bit so the climate problems are not so bad. And then we're going to adapt so that we can cope and survive with the problems we're causing.” That's what realists will normally say. All right? So suppose you live in a low-lying coastal area and sea levels are rising. One thing you do is try cutting back on carbon emissions, but you're not going to cut back enough to stop sea levels from rising. So sea levels are rising. What can you do to save your city? Build? What do you build? Well, the Netherlands is below sea level. What? But still, the country is dry. How do they do it?

They build what? What's that? Yeah. Dams, or is that a special name when you have something that just keeps the sea out? Here, let's do it. All right. All right. Let's see. Is that a good translation? A sea wall? This is where you put a big wall at the sea to keep the ocean from flooding your area. All right, so that's what you do. Hay-dee? It's okay? Hay-dee? It's all right. Okay, good. I'm learning, right? Learning. Okay. All right.

So yeah, if you've got a low-lying coast area, you build a sea wall, all right? And then even though the sea levels rise, you don't flood. All right? That is something that we're likely to do. Something that people talked about and many people were very worried about it and, say, we got to cut back on our carbon emissions. Let's say, “look, it's not realistic to only cut back on emissions. We're going to have problems and we're going to get ready for them. So let's build sea walls in areas that are low-lying, there's a lot of people, we'll do it.” Okay? All right. But still, when you hear this, what do you have to say about that? Adaptation. That sounds really risky. When disaster strikes, so what makes us think we can adapt? Seems unlikely, right? It's like there's going to be an entire horrible problem. I want us to adapt. Like, imagine we find out an asteroid. An asteroid. Now I'm curious. All right. Yes, asteroid. Is that a good translation?

All right, we have an asteroid coming for Earth and someone said, oh, we'll just adapt. We're going to adapt to an asteroid? How are we going to adapt? It's crazy. It's an asteroid. It's like what? Adapt or die. Those are our options. Asteroid killed the dinosaurs. You've heard this. All right? Yes. So asteroid comes, hits the earth. You got two options with an asteroid. One is it hits the ocean and it causes the biggest tidal wave the world's seen in a million years, right? That's pretty bad, right? Other option is it hits the land, kicks up an incredible amount of dirt, and it blots out the sun for a few years. So yeah, if you're lucky, it hits the water, actually.

That only kills like 10% of humans. If it hits the land, then could kill all of us, or almost all of us. Okay. All right. So if there's an asteroid coming and someone said, don't worry, we'll adapt. You would probably say, what? Is there another plan? Is there another plan? Right? You've seen movies where human beings go and launch a spaceship to go and blow up the asteroid before it gets to Earth using nuclear power every time. Every movie where a spaceship goes to blow up an asteroid, they use nuclear weapons on it because those are the best weapons, the weapons that could destroy an asteroid if we're lucky. All right?

Anyway, all right, so if disaster strikes, if we have sea levels rising a hundred feet, can we really adapt to that? All right. And it's one where I think it's very natural when you hear this word to be like, ooh, that sounds like wishful thinking. And where I've been making fun of people for living in a fantasy world, right? The fantasy is thinking that we can go and raise the temperature of the earth a hundred degrees and still survive.

Say, yeah, that doesn't sound very likely to work. How are we going to survive when it's 200 degrees? Seems really tough. All right, so anyway, what Epstein says is this. Don't think of adaptation as some new thing that we've never done before. It's not true that we have not adapted before. It's not a new process. It's not untested. Here's the real story. Earth is naturally a very dangerous place for human beings. Earth is naturally deadly for humans. And we have through amazing efforts, made it seem like it's safe, but it's not. If you've ever just been all by yourself in a natural area and you don't have a phone, you don't have any way of contacting people, it's hard not to start realizing, oh wow, I would die here very quickly unless I could get back to civilization. You don't know how to get food. You don't know how to build a fire without matches. Right? You can't build a shelter. You will be food for animals in a lot of places on earth if you are just one person by yourself. Earth is naturally very dangerous.

And we have been adapting to this very dangerous place for thousands of years. This is the real story. All right? So imagine living here in Virginia last winter, but you only have wood and dung for heating. What is that life going to be like? Pretty bad. And then you realize, oh yeah, that also means I'm going to have to go and store all my food for the winter without any refrigeration. How am I going to get that? And it's like, well just go to the store. Yeah, well, the store is also based on wood and dung, so, oh yeah, that sounds really bad. It sounds like we might die. And Virginia is not the worst climate in the world, where we barely even had any snow this winter, but still, we had people living below freezing. Imagine you just have these clothes. You probably would freeze used to death in these clothes. So it's like, all right, can you skin animals? Do you know how to do that? This is all... Would you even be able to hunt an animal successfully? Right?

And the animals around here, they don't even have very good fur. We'd have to first go north to where there's the animals with good fur and then bring it here. All right. So that's the problem. The world is naturally very dangerous. Nature is not a nurturing mother here to go and take care of us and provide for our needs. Nature is actually very harsh. If you don't plan ahead or rely upon other people and know what they're doing, you're going to die. And yet we're alive. So actually it looks like human beings are quite good at adaptation because we've already turned the world into a place that is almost fatal into one where we barely even think about dying. Anyone worried about dying today? Like, “hey, I'm going to make it. You're doing fine.” Now, remember now, how good was the adaptation in earlier periods? Well, take a look at that. A hundred years ago, the adaptation wasn't so good. So we had almost 2,500 people out of, was it out of a million? Out of a million people dying every year from climate rate disasters.9

We don't have data from before, but it was probably a lot worse. Probably a lot worse, yeah. So yeah. So climate-related disasters should also include drought when there's no rain. Right? So it should include times when you just don't get enough rain for your crops. So there's almost no food. And then people starve to death. That's climate-related disaster, right? Or flooding. You can get flooding that wipes out all your crops, too. So probably in earlier periods, it was much higher all the way up to the ceiling for climate-related disasters once you remember agriculture depends upon nature and other periods. Today, if we get no rain, how do we still get food? How do we still grow food? Just turn on the sprinkler. Turn on the sprinkler. And then how do we do that? Well, we collect water in large reservoirs, and then when we need it, we just turn it on. This is not what human beings did for most of human history, right?

Okay, here we are. Okay. All right. So anyway, Earth is naturally dangerous. We've been adapting to it for thousands of years. Even this area is actually a terrible place to live without modern technology. So yes, stop thinking of adaptation as something new. All right? Now, the adaptation was still pretty bad up to a hundred years ago. Now we're doing amazingly well. At least right now we're fine. And this is one of the really great points that Alex makes in his book. If someone says, things are great now, but disaster is coming, it's like, all right, this person at least understands reality. They looked at the present. They admitted that things are fine now, and then they say yes, but things are going to change. And he says, “look, I'll talk to that kind of a person. That person could be a reasonable person.” But here's the person that is not worth talking to.

The person who says the climate is a disaster right now. We are already in the apocalypse. That person doesn't know the facts. That person looks at a world that is better than ever and claims it's hell. Person's a fool and person's a fool, and you probably have better things to do than to listen to a person like that. So anytime someone says, look at the news, the climate is already disaster. Yeah, guess what? If people had news 200 years ago, the stories would be a lot worse. Things are better than ever. The real reason why there's always bad stories in the news is the world is 8 billion people. Furthermore, we have fossil fuels to fly the journalists to wherever the worst thing is happening. So then everybody gets to find out what the worst thing happening is. With 8 billion people every day an incredibly sad thing happens on Earth, but doesn't show the world is getting worse. It just shows we have a lot of people.

So a lot of people, one in a billion story. That's a terrible story. But fortunately, it is not going to be your story with near certainty. All right? So anyway, previously our adaptation wasn't that good. Now our adaptation's quite amazing, amazingly good. It's one of the least worrisome things, the climate. All right? And he says, so how do we just change the world, stop talking about adaptation, which makes it sound like it's something that's novel and weird. And he says, how about we call it this? And he says, let's call it climate mastery. Climate mastery, something else. All right, what's the idea of climate mastery? The idea is we started off with a terrible environment, namely regular, unimproved nature, which is deadly and miserable for humans. And then we used our technology powered by fossil fuels to fix it, to fix it.

Basically what nature gives us is a broken machine and human beings have fixed it. And by fixing it, we have made things good for the first time. The idea that unimproved nature is good for humans is just ridiculous. If there was some previous time where primitive humans lived in peace and harmony and everything was wonderful and they just picked fruit off the trees, there's never been a time like that. Those primitive people are living in great danger. And now we are the ones that are living in the best times ever. All right, so Epstein's point.

So we don't just use fossil fuels and then struggle to adapt to a problem that we unleashed, for the first time. All right? So it's not like the world starts off great. We use fossil fuels, we ruin it, and then we try to undo the what? All the ruin. That's not the correct story.

He says the correct story is this; fossil fuels turn the world from one kind of dangerous place into a different kind of dangerous place. It's always dangerous. But in both cases, what really makes the difference isn't the danger of nature, which is always there. What really makes the difference is whether we are consciously going and using our technology to go and make it good for humans. All right. So yeah, we change Earth from one dangerous place to a different kind of dangerous place. And here's the new thing. We've already used fossil fuels to get rid of almost all the familiar dangers. Throughout all human history, we've had to worry about flooding. Has anyone here ever been flooded? The worst flooding in Alexandria 20 years ago during the hurricane, but go back a couple weeks later, things are fine again.

All right. How about hurricanes? Blizzards, extreme cold, extreme heat. These are all horrible problems that human beings have dealt with throughout all human history until today. And today we've got climate mastery. We've got technologies that almost totally solve these problems, right? Oh my God, it's a really hot day. I guess I'll just stay inside in the air-conditioned building. Human beings throughout history were not able to say that. Even the King of France could not just say, “hey, turn on the air conditioning” 200 years ago." Have you ever wondered what would you do if you were the King of France during a horrible heat wave? Probably go and hang out in a cathedral and you've been in cathedrals. They have all that stone, they're naturally cold. Or I think I would actually have a giant cave palace that I could go to.

Some caves are cold. So if I were the king, I would take care of myself. But most of them are just there. Oh God, fan me more. The servants with the fans, fan me more. That's all they got. Who fans the guys fanning the king? Nobody. They just suffer. All right, so we already used fossil fuels to eliminate practically all the familiar dangers. What does this show? It's not just a matter of luck. If we had solved half the problems, then you'd say, all right, well half the problems are solvable, half are not solvable. We've solved basically all the problems. It's like, wow, human beings with modern technology, with fossil fuels, we can deal with almost anything the world can give us. Human beings could survive in Antarctica and do. How? Right? You wouldn't survive there with wood. You survived there with fossil fuels.

All right, so here's the real question to worry about. The real question to worry about is this. Are the new dangers we're going to cause with carbon emissions outside of the range of what human beings have already solved? Are we going to cause problems that are so much worse than what we already deal with that then we will fail? And here's the dilemma. We handle a huge range of dangers. Human beings are capable of surviving comfortably at the equator. We're capable of surviving comfortably in the Arctic and not just at the best time in the Arctic or the best time in the equator. We're capable of surviving year-round in all of these different places on Earth that have an incredible range of temperatures. So about the hottest temperature ever recorded on earth is naturally occurring is I think about 135 degrees Fahrenheit. And the coldest temperature is, I think below negative 50 degrees Fahrenheit. So basically, human beings are capable of dealing with a 200-degree temperature range. We can do that.

It's pretty impressive. So it's not like we've just managed to make life comfortable in Virginia. We've made life comfortable in every inhabited climate, not just safe, comfortable. Okay, so we've handled a lot already. So now when you step back and say, wow, human beings are actually really good at this. We are really good at this. We have managed to deal with terrible problems, so we could probably deal with some others. How much are we going to move? Okay. And again, if you take a look at estimates of how much a further doubling of carbon emissions will do to the climate, so normally a low estimate is one degree Celsius, medium estimate is like two degrees Celsius. So this is warming the whole world by say, two to five degrees Fahrenheit, very negative pessimistic estimates we'll get up to 10 degrees. All right. It's like, well, 10 degrees, is that really bad? Well, we already know how to deal with everything in this current large range. Why can't we just use climate mastery to adjust? All right, we'll go and we'll put less into heating technology, more into cooling technology.

Seems like it would be doable. Now the important thing to understand, by the way, about carbon emissions is that it is not a linear effect. It is a logarithmic effect. What does this mean? It means that you have to keep doubling carbon dioxide to get the same increase in temperature. So if one doubling raises it by two degrees Celsius, you need to double it again to increase it by four, to get it up by another two degrees, you need to double it yet again to get up to two more degrees. So it's actually built in. It's not as hard to deal with as it seems because it's not a linear function. It is a logarithmic function. All right, so now here is the last thing that to talk about tail risk. This is what a lot of really smart people talk about when, let's say, all right, so here this is danger, and here is [Bryan Caplan is drawing on the board]. Let's do this. Danger here and probability.

All right. When people that are not crazy, when people that are reasonable talk about climate risk, well, they'll say well “look, all right, there's some chance that there's barely any danger.” All right? So likely this will be like no danger. All right? So there's probably your reasonable chance that there's barely any problem. And then the most likely scenario is that there's some moderate danger. But then say there's that. What's that? That is called tail risk. See, how it looks like a tail of an animal? Animal like a dog's tail. Tail risk. Is that a good translation or is that bad? Tail risk. That's a terrible translation. All right, what if we just do that?

How's that? All right, so that's like the tail of an animal, right? A monkey has a tail or a dog has a tail. All right? You see here, this is the tail. It's this long thin thing at the end, right? And there, let's see, there's a book called, let's see. Blanking on the book. Anyway, so there's a book about climate change that a guy said, well, God, this book is so great I will bet you that it will change your mind and make you a lot more worried. And he actually bet me $500. And I said, “look, it's hard to change my mind. Just warning you.” And he said, “no, the book's so great.” And yeah, that didn't change my mind, but the book was about, and I got $500 to not change my mind to read a book.

All right. Okay. Now this is an offer I often make to people. They say, oh, this thing's so great. And it's like, yeah, that sounds crazy. No, no, no. But you're wrong. It's really wonderful. All right, tell you what, let's bet. If you win, then I admit that I was wrong, the book was great, and then I will pay you some money. But if you make me waste my time and read a book, then I decide it's not good. You don't have to pay me money. All right. So it's basically, it's like my fee to read a book I don't want to read. Couple people have done it, but not many. Anyway. So tail risk. This is saying, “look, there is some small chance of total disaster.” People sometimes call this an existential threat. An existential threat. It will wipe us off the face of the earth. It will destroy the human race. Let's see. Is that... How's that for translation? Does that make any sense? All right, so that's like it will destroy us.

Human beings will be destroyed. All right? The existential threat, this is what people worried about. If the climate just happened, if our measurements are wrong and we actually raise the temperature of Earth to 200 degrees, we'll be able to survive. Probably not. I think we're going to die. Maybe we could all move to Antarctica or something, and a few of us can survive in Antarctica, but most of us won't make it right. We'll be dead. Okay. All right. Okay. All right. So isn't there at least some small chance of some tail risk? And, if you’re honest, there's always some chance. All right. So what is a disaster that is so bad that our climate mastery cannot handle it? Even though we know how to go and make human beings safe and comfortable in Antarctica, and at the equator, we know how to survive hurricanes, floods everything else. This is going to be beyond that. This is going to be beyond our capability. So far beyond we just cannot go and figure it out. All right? So is that possible? Yeah, sure it's possible. Sure, it's possible. But here's the main problem. There are multiple disaster scenarios.

There are multiple disaster scenarios. Here's a disaster that I worry about. What if the world's governments outlaw fossil fuels before we have any realistic replacement? What happens then? Yeah, that will kill billions of people, too. If you go and just say, “hey, look, we're just going to get rid of this, the only way that we're going to go and really adapt and switch over, we just have to stop taking the drug of fossil fuels and then see what happens.” And if we do that, I think that's going to be a total disaster, will kill billions of people. Is that likely? I don't think that's likely. But tail risk. If we keep brainwashing kids thinking that solar and wind are ready to go and power our civilization, could they go and vote for some lunatic that thinks that this is true and then kill billions of people? I don't think it's likely, but it's a tail risk. It is an extreme danger that we can imagine. And to say it's impossible is also wrong.

Now, here's a more likely scenario. What if instead of taking fossil fuels away from rich countries, which is hard, people don't want to go back to living in the stone age, but what if we just make the third world stay in poverty for a few more decades? Imagine that in 1975 Deng Xiaoping said, yeah, well, I'm worried about global warming, so we're just going to keep using primitive technology. We're not going to go and adapt to coal, yeah, we're not going to do fossil fuels. We're not going to do nuclear. We're just going to keep doing wood and dug. Imagine if Deng Xiaoping had said that, then China would still be extremely poor today and none of you would be here, probably. You would still be in a very desperately poor country. Have you talked to grandparents about how hard life was in China when they were young?

Do your grandparents say, when I was young, we were starving? Yes. You have heard this. All right, yeah. And it's true. It's true. There was horrible famine in China in the 1960s. I believe the worst famine that ever happened on earth. All right. So yeah, taking energy away from rich countries is going to be pretty hard, but just preventing it from ever happening in poor countries, that's a lot more realistic. In a way, a lot of... Well, at least some of what groups like the organization, like the World Bank or the IMF, do is they say, well, we'll go and give money to the dictators in the country to not do fossil fuels. And then the dictators say, okay, great. Well, I can have my own generator, I'll be fine, but we're going to do renewable energy here in Haiti, right? And then what happens to Haiti? Things stay really bad. So it's going to be a lot easier to prevent poor people from getting energy in the first place.

All right. And what's so dangerous about that? Well, of course, it's just keeping people trapped in poverty and misery for extra decades. That's bad. But I also have a theory. Just let me tell you. Here is my theory. When do you get, right now, if you look on Earth, despite the Ukraine war, war has almost disappeared from Earth, and it's been a long time since there's been any serious war on the planet. Basically, World War II is the last really serious war on earth. And if you look at the numbers, war has been going down for a really long time. Before that, there's World War I and there's World War II, terrible, horrible wars. Why has the war gotten so peaceful? This is my view. My view is that when people are rich, they are cowardly. Rich people don't want to die.

Poor people, their lives are so hard, they'll take chances and see, maybe there'll be a war, maybe this will happen. But when people are rich, they are cowardly, which is good, which is good because when all countries are cowardly, the world has peace. When countries have brave men ready to die, then you have war. All right. Now, but here is the key assumption of my view. It's not really whether you are rich now that matters. It's whether you grew up rich. So if you have always been rich, then you're cowardly. If on the other hand, you were poor for most of your life and then your country gets rich, this is where you still have these early values, these pre-modern values where you have a low value in human life where you're willing to take risks. And this is my whole story about the world wars.

The two wars happened when for the first time, humanity was rich and had the power to destroy entire countries, but still had the values from an earlier time when life was cheap and people were really willing to go and bear great danger. All right. So really what do we want to do if this is right? What we want to do is we want to get the whole world rich very quickly because, during the first 30 years of countries being rich, that's the danger zone. That's when they have the power to do great evil. But they have not lost the courage to do great evil. It's like China. On my theory, China is right about now, you are leaving the danger zone. You're leaving the danger zone. The danger zone was during, from around 1980, 2010. That's 30 years where you are.

You're getting rich. You've got the power to do great evil, but you still have people remember the old days when people died and nobody cared. All right, so now you're leaving the danger zone. My view is we want to get all countries out of that danger zone. We want everyone to be rich quickly. And then there's always a period. Come on, don't have World War III. Don't have World War III, and then, all right, fine, we got through the danger zone and now things will be okay. All right. So we messed up with World War I and World War II. It's really bad. All right. Again, you couldn't have had wars like that a hundred years earlier. We just didn't have the technology to go and kill people like that before. But then we did. But anyway, now we have even worse technology than we had in World War II.

Much worse. But we don't want to use it because it's like, well, I don't know, someone could get hurt. So that's my story. So the disaster that I'm worried about presenting is let's prevent World War III. That seems like a really bad disaster. So, best way to do that is just to get countries...the world, more rich quickly. And to do that, we need countries to use cheap...We need cheap, affordable energy for the planet.

Popular links

EnergyTalkingPoints.com: Hundreds of concise, powerful, well-referenced talking points on energy, environmental, and climate issues.

My new book Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas—Not Less.

“Energy Talking Points by Alex Epstein” is my free Substack newsletter designed to give as many people as possible access to concise, powerful, well-referenced talking points on the latest energy, environmental, and climate issues from a pro-human, pro-energy perspective.

The US still imports significant amounts of oil for its refining industry, making it a net oil importer, but the products in turn get exported.

America is a net exporter of petroleum but remains a net importer of crude oil so far.

U.S. Energy Information Administration - Oil and petroleum products explained

The Watts Bar Unit 2 nuclear power station was completed in 2016 after being suspended in 1985. It was originally licensed in 1973.

Since then Vogtle Unit 3 and 4 in Georgia came online but with significant delays and budget overruns.

U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission - History of Watts Bar Unit 2 Reactivation

World Nuclear News - Watts Bar 2 steam generator replacement completed

Reuters - Vogtle’s troubles bring US nuclear challenge into focus

Solar and wind never work the same way controllable electricity generators like fossil-fueled power plants work. They never provide the exact amount of electric load the power grid requires on their own.

Powering Japan with solar electricity from Spain is extremely difficult to do because of the transmission losses involved over that distance. It’s not clear whether it could be done with unlimited funds from an engineering perspective.

Steel is often made using electricity, e.g. using induction or electric arc furnaces. However, metallurgical coal is used as an efficient source of heat and carbon for creating steel from iron ore.

UC San Diego - The Keeling Curve

For every million people on earth, annual deaths from climate-related causes (extreme temperature, drought, flood, storms, wildfires) declined 98%--from an average of 247 per year during the 1920s to 2.5 per year during the 2010s.

Data on disaster deaths come from EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium – www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir).

Population estimates for the 1920s from the Maddison Database 2010, the Groningen Growth and Development Centre, Faculty of Economics and Business at University of Groningen. For years not shown, population is assumed to have grown at a steady rate.

Population estimates for the 2010s come from World Bank Data.

While nuclear fission bombs and nuclear fission reactors share some similarities, a reactor cannot explode. Nuclear reactors use fuel that only allows a very slow chain reaction to be sustained, which makes it impossible to instantaneously release most of the energy content, which happens in a nuclear bomb.

Most coal mining deaths on Earth occur from fatal injuries in China. But the fatality rates have massively declined since the early 20th century. While respiratory diseases still play a role, they are mostly a problem of lackluster discipline in wearing protective gear and low safety standards in developing countries.

Facts and Details - COAL MINER DEATHS IN CHINA

UC San Diego - The Keeling Curve

For every million people on earth, annual deaths from climate-related causes (extreme temperature, drought, flood, storms, wildfires) declined 98%--from an average of 247 per year during the 1920s to 2.5 per year during the 2010s.

Data on disaster deaths come from EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium – www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir).

Population estimates for the 1920s from the Maddison Database 2010, the Groningen Growth and Development Centre, Faculty of Economics and Business at University of Groningen. For years not shown, population is assumed to have grown at a steady rate.

Population estimates for the 2010s come from World Bank Data.